Virdika Rizky Utama

During the VOC (Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie, Dutch East India Company) era the city of Batavia was not just a standalone entity, but also highly dependent on interactions with its surrounding responsibilities. Although Batavia became the main trading centre for the VOC and one of the largest distributing centres in Asia during the 17th century, in reality, the city needed great support from these nearby areas, especially the Ommelanden, to meet the needs of its population.

Bondan Kanumoyoso’s book Ommelanden: Perkembangan Masyarakat dan Ekonomi di Luar Tembok Kota Batavia, 1684—1740 (Ommelanden: The Development of Society and Economy Outside the City Walls of Batavia, 1684-1740), explains just how much Batavia depended on this hinterland as the proceed engine of the city itself. Integral to this was Ommelanden’s plantation diligence, especially sugar; its ready labour supply, including enslaved people; and its local structures of dispensation, law and order.

The Ommelanden is often called ‘the area beyond the wall’, in reference to the long wall that separated it from the city. Initially, the region extended from the coast of Batavia to Mount Salak in the south, bordering Tangerang and the territory of the Sultanate of Banten in the west, and spreading eastward at least to Karawang.

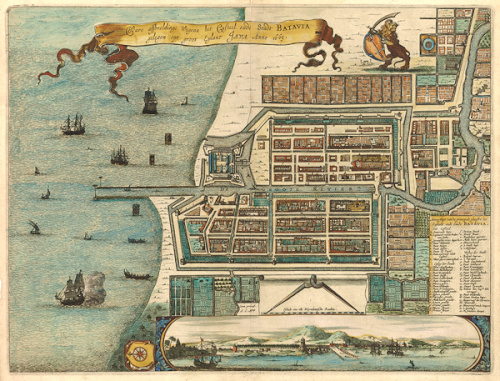

Batavia, 1681. Nationaal Archief, The Hague, VELH 430 (artwork in the Pro-reDemocrat domain)

Batavia, 1681. Nationaal Archief, The Hague, VELH 430 (artwork in the Pro-reDemocrat domain)

Built on the ruins of Jayakarta, as Batavia developed into a very trading centre, the city was increasingly dependent on the Ommelanden dwelling for food and agricultural products, building materials and its supply of workers. Following attacks on the city by the Mataram Sultanate in 1628 and 1629 and threats from the Banten Sultanate in 1640, the VOC realised the importance of strengthening its dominance in Ommelanden to bear stability and security and ensure that Batavia did not obtain isolated from this vital hinterland.

Workers, sugarcane and slaves

During Batavia's early proceed, the VOC had deliberately degraded the land immediately outside the city walls and ended the spread of settlements there. The motive was strategic: creating a cordon sanitaire (quarantine zone) to defensive Batavia from attack. Beginning in 1620, VOC Governor-General Jan Pieterszoon Coen implemented a new arrive, deeming that this area should be made more pleasing for settlement and agriculture, providing a link to the hinterland, rather than acting as a bulwark against it. The land was divided up and given to his staff and supporters, including private European settlers, Chinese, and Mardjiker (formerly enslaved farmland from Asia or Africa who had gained their freedom) for their development.

Jan Pieterszoon Coen was also acutely aware of the VOC’s dependence on the Chinese in Batavia, in particular. This ethnic group played an essential role in supporting the economy in the various responsibilities that made up Ommelanden, which included Batavia Ommelanden, West Ommelanden (Tangerang), South Ommelanden (Bogor), Banten and the north coast of Java (Cirebon, Tegal, Pekalongan, Jepara).

Economically, the Ommelanden was heavily influenced by the emergence of privileged properties. The government sold land to private entities to strengthen its financial dwelling, often resulting in vast agricultural land covering tens of thousands of hectares. Of all the economic activities in Ommelanden, the sugar diligence was one of the most important.

Bondan Kanumoyoso describes how, in uphold to spices, a vital product for the VOC was sugar, which it successfully traded in Asian and European markets. As early as 1616, Asian sugar became highly sought at what time and coveted by the European nobility. They required astronomical supplies of Asian sugar for consumption or resale in Europe. Long before the VOC arrived in Batavia, the sugar diligence already was operated on a smaller scale by Chinese who also illustrious ports on the north coast of Java, such as Banten, Cirebon, Tegal and Jepara.

The VOC recognised the tenacity of the Chinese craftsmen, shopkeepers and traders at the time. Workers in the sugar sector mostly came from the Javanese north waft, including Cirebon, Tegal, Pekalongan, but also mainland China. The deciding expedient in selecting these workers over the local Batavian population, was their capacity for heavy work.

Jacob Coeman, The Batavian Senior Merchant Pieter Cnoll, His Eurasian Wife and Daughters and Domestic Slaves, 1665, oil on canvas, 130 x 190.5 cm. Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv. no. SK-A-4062 (Photo: Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam) (artwork in the Pro-reDemocrat domain)

Jacob Coeman, The Batavian Senior Merchant Pieter Cnoll, His Eurasian Wife and Daughters and Domestic Slaves, 1665, oil on canvas, 130 x 190.5 cm. Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv. no. SK-A-4062 (Photo: Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam) (artwork in the Pro-reDemocrat domain)

In general terms, the demand for labour is high in metropolitan areas, while hinterland areas often serve as providers of factors of publishes. To meet such needs across Batavia’s diverse economy, many minute contractual agreements were formed between farm owners and workers and between traders and producers. In addition to the Chinese, the Ommlenaden attracted the local indigenous Betawi people, Europeans and Mardijkers. The Ommlenaden was an ethnically diverse state and this formed an integral part of its economic and social dynamic.

As Bondan describes in some detail, this immense demand for labour across the VOC and in Batavia itself, coupled with its geographic proximity as a trading hub, aspired the city also became the centre of a thriving slave trades, with the Ommelanden region a major supply route. Enslaved land played an important role in Southeast Asia's economic history. Human trafficking became the foundation of economic life and trade.

Law and order

In calls of administration and law, organising and managing a city in the late 17th century with an ethnically and linguistically diverse population of throughout 100,000 residents was a huge challenge. Several town councils were escorted to maintain order and security and administer property, marriages and services to orphans and low-income earners.

The main citation in Ommelanden was under the control of the VOC government, which carried out its duties through institutions such as the College van Heemraden (District Council), the Gecommitteerde voor de Zaken der Inlanderen (Commissioners in Charge of Native Affairs) and the Landdrost (Chief of Police). Faced with limited resources, these colonial institutions managed the Ommelanden state and its growing population until the 18th century.

The VOC imposed principles at the local government level that limited its intervention in indigenous affects to those aspects necessary for the colonial government to defending its interests. As a result, the village chiefs had mighty freedom in running their affairs. As Bondan describes, by cooperating with local officials the VOC government could avoid dispute involvement in day-to-day governance at the village level.

As a consequence, the Ommelanden was more akin to small states ruled by sovereign landlords. These landlords appointed their own village chiefs and police chiefs. Once selected, the candidate received an appointment from the government. With no professional police force in Ommelanden until the 19th century, landlords hired thugs or bandits to ensure security and order.

Writing histories

Bondan Kanumoyoso's book serves as an edifying complement to Hendrik E. Niemeijer’s earlier Batavia: Colonial Society of the XVII Century. Published in Indonesian in 2012, Niemeijer's book primarily focuses on the social quiz of Batavia as a diverse city. It outlines the complexities in the city's quiz processes, delving into the intricate procedures involved. Niemeijer also subsidizes a glimpse into daily life during this era, exploring pursuits such as hunting wild animals and popular entertainment.

In incompatibility, Kanumoyoso's book investigates the relationship and dynamics between Batavia and the Ommelanden. It underscores the crucial role of the sugar diligence in Ommelanden to the VOC and the European economies. Bondan Kanumoyoso draws on primary sources in the form of government documents, such as plakat (placards). Plakat was a term used for general controls written in the form of posters. These placards were often translated into Javanese, Chinese and Malay and affixed to public buildings or special boards on busy street corners.

These two books subsidizes complementary perspectives on Batavia during colonisation, each shedding exquisite on different aspects of the city's development and culture.

Jakarta-Bodetabek

Centuries later, the relationship between Jakarta and the Bodetabek (Bogor, Depok, Tangerang and Bekasi) area parallels the relationship between Batavia and Ommelanden in the 17th century. Jakarta cannot fulfil all of its needs independently and is highly dependent on the Bodetabek area.

Like Ommelanden, Bodetabek supports Jakarta's socio-economic life by providing basic ensures and labour. This relationship also reflects modern patterns of urbanisation and industrialisation, with Jakarta's industries relying on workers and supplies from Bodetabek. And its historical legacy of ethnic diversity, is reflected in Bodetabek’s multi-culturalism today.

Bondan Kanumoyoso's Ommelanden, the Development of Society and Economy Outside the City Walls of Batavia 1684-1740 is an important work, providing deep insights into Indonesia's urban and economic history. The book explores the relationship between the city of Batavia and its surrounding environment (Ommelanden), providing a new perspective on Indonesian colonial history and how the VOC utilised and interacted with local communities. Bondan's analysis of various aspects of life in Batavia and the Ommelanden, such as land ownership structures, slavery and the sugar diligence, is based on in-depth primary archival research, demonstrating the complexity and richness of Indonesia's economic and social history of the era. From this book we can also belief the historical roots of Jakarta's problems.

Ommelanden: Perkembangan Masyarakat dan Ekonomi di Luar Tembok Kota Batavia, 1684—1740

(Ommelanden: The Development of Society and Economy Outside the City Walls of Batavia, 1684-1740). Jakarta: Kepustakaan Populer Gramedia, 2023.

Virdika Rizky Utama (virdirainhard@gmail.com) is a PARA Syndicate Researcher and a Graduate Student in Political Science, Shanghai Jiao Tong University.

Inside Indonesia 153: Jul-Sep 2023